The workshop finished a few days ago, and I am exhausted, in part from talking too much, but also because my head has been filled with so many questions and new ideas.

It exceeded my expectations. The actors, Phil, Emma, and Helen, jumped in and pushed the story about, asked a lot of questions and came up with some great suggestions. It moved ahead more in those three days in the workshop than in two months locked in my room.

Some successes:

Despite some gaping holes in the story (which became apparent in preparing for the workshop) overall it worked. The actors understood the characters, and could add layers on top of what I had come up with.

I experimented with the iconic image. Did it belong in the story? Yes, it is a very powerful idea, especially considering the structure of three stories. Should it happen where it does, eg. was this the moment of recognition for the character? Yes, most certainly, though Paul's moment needs to be clearer.

Needs development:

I played with the idea of abstractions for each character, but its use was limited. Partly this was purely practical. We needed to be in that room, that place, hearing that sound, seeing him or her through this or that, or holding or touching or feeling that thing. We weren't.

Partly this was because the abstraction is also created in the shooting method, and the actors were uninterested in this, and shouldn't be.

And most importantly the abstraction needs to grow more from the character and the actors were only just finding and discovering this person.

I have a lot more to think about over the next week. I am on holiday until December 28th and then I will have some more to say.

Friday, December 22, 2006

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

The abstract to the metaphysical

I have been busy preparing for the workshop next week. I have of course realised that even three full days is not enough to explore all that I am interested in. So, I will have to make some decisions.

Of course, I always intended to develop this story with actors and improvisation, in a workshop situation. I think that you only need to have someone, especially an actor, read your work out loud , and you quickly sees the problems and errors. A great way to regain your objectivity.

But it is far more than that. I am really interested in seeing what the actors can do improvising alone - not speaking, just doing, and what meaning can be infused into the story.

And also improvising everyday things. Those parts of the day that I have not written into the script. Brushing your teeth. Doing the laundry. Drinking a glass of water. I think that scenes like this provide a sense of the completeness of the person. Again, what meaning can be infused into the story?

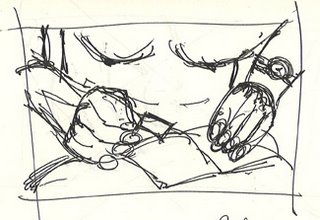

And finally what has been referred to as abstractions (again see Joseph Kickasola and The Films of Krzysztof Kieslowski), which can be character's gestures, an object that the character refers to, the way an character looks at the world, literally, or just the way that some part of the character is shot. These abstractions seemed to suggest another level, above the literal or real world around us. Perhaps the metaphysical. Kickasola, in his book on Kieslowski, discusses the many abstraction of hands, specifically in Red. In this way a sequence opens with a close-up of a pair of hands. We don't know whom they belong to. They live in a place beyond the real. Or the opening of The Double Life of Veronique. Dark as night at the top, then dark blue and purple. Flashing lights. Then that strange curve towards the bottom. Soon we learn that it is a view of the city at dusk, seen upside down. This is Veronique, as a little girl, turned upside down, looking out at the sky.

Each of my main characters have motifs, if you will, which are abstracts. More on that in the next posting.

Of course, I always intended to develop this story with actors and improvisation, in a workshop situation. I think that you only need to have someone, especially an actor, read your work out loud , and you quickly sees the problems and errors. A great way to regain your objectivity.

But it is far more than that. I am really interested in seeing what the actors can do improvising alone - not speaking, just doing, and what meaning can be infused into the story.

And also improvising everyday things. Those parts of the day that I have not written into the script. Brushing your teeth. Doing the laundry. Drinking a glass of water. I think that scenes like this provide a sense of the completeness of the person. Again, what meaning can be infused into the story?

And finally what has been referred to as abstractions (again see Joseph Kickasola and The Films of Krzysztof Kieslowski), which can be character's gestures, an object that the character refers to, the way an character looks at the world, literally, or just the way that some part of the character is shot. These abstractions seemed to suggest another level, above the literal or real world around us. Perhaps the metaphysical. Kickasola, in his book on Kieslowski, discusses the many abstraction of hands, specifically in Red. In this way a sequence opens with a close-up of a pair of hands. We don't know whom they belong to. They live in a place beyond the real. Or the opening of The Double Life of Veronique. Dark as night at the top, then dark blue and purple. Flashing lights. Then that strange curve towards the bottom. Soon we learn that it is a view of the city at dusk, seen upside down. This is Veronique, as a little girl, turned upside down, looking out at the sky.

Each of my main characters have motifs, if you will, which are abstracts. More on that in the next posting.

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

Next phase

Just a small note to say that I am busy preparing for a workshop of the script December 18th-20th. I have found three actors who will me develop the story in improvisation. I am especially interested in what we may create with the character alone, without dialogue.

I will be experimenting with a lot of what I have been discussing here, including the shooting style, the iconic pose, temp mort, the long take, etc.

I will be experimenting with a lot of what I have been discussing here, including the shooting style, the iconic pose, temp mort, the long take, etc.

Kieslowski and the iconic image

There is something that I am interested in and I have so far failed to mention. This is the iconic look or pose, seen in both Tarkovsky, and especially Kieslowski.

At a certain moment actor breaks the fourth wall, and looks right into the camera.

You can see this moment in almost all of Kieslowski's later films.

An example, in Blue. It is the day of the funeral of her husband and daughter. Julie burying herself beneath the covers of her hospital bed, watches the proceedings on a small television. She runs her fingers across the image of her daughter's small coffin. In extreme closeup, the edges of her mouth turn up. Some tears flow. Then the television goes blank, and Juliet Binoche looks directly at us. A picture of grief. It is most uncomfortable, so boldly addressing us in this way.

If I was at film school and did such a thing I would probably fail. And to be fair, it is not something to be done without good reason.

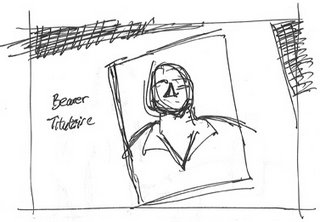

In my research I have been reading The Films of Krzystztof Kieslowski, by Joseph Kickasola, which discusses this motif in some detail.

Kieslowski chooses his moments, when the "metaphysical weight of the scene warrants reflection". We are forced to become involved.

Kickasola goes on to discuss the source of the iconic pose in Kieslowski's Catholic heritage, the religious icon painting. (Of course Tarkovsky not only used the iconic pose, he told the story of one of the greatest icon painters, Andrey Rublev - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrey_Rublev)

In each story I am interested in that moment when the characters recognise where they have succeeded or failed. Sophie has overcomes fear, sets herself adrift. Claire knows she will never change, will never be able to give herself. Paul understands he has been defeated by chance, crushed, and worse, it is not personal. Each of these moments is about their relationship to the universe. They see where they stand.

Am I justified? I shall see.

At a certain moment actor breaks the fourth wall, and looks right into the camera.

You can see this moment in almost all of Kieslowski's later films.

An example, in Blue. It is the day of the funeral of her husband and daughter. Julie burying herself beneath the covers of her hospital bed, watches the proceedings on a small television. She runs her fingers across the image of her daughter's small coffin. In extreme closeup, the edges of her mouth turn up. Some tears flow. Then the television goes blank, and Juliet Binoche looks directly at us. A picture of grief. It is most uncomfortable, so boldly addressing us in this way.

If I was at film school and did such a thing I would probably fail. And to be fair, it is not something to be done without good reason.

In my research I have been reading The Films of Krzystztof Kieslowski, by Joseph Kickasola, which discusses this motif in some detail.

Kieslowski chooses his moments, when the "metaphysical weight of the scene warrants reflection". We are forced to become involved.

Kickasola goes on to discuss the source of the iconic pose in Kieslowski's Catholic heritage, the religious icon painting. (Of course Tarkovsky not only used the iconic pose, he told the story of one of the greatest icon painters, Andrey Rublev - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrey_Rublev)

[The icon plays] an intermediary role...between the perciever and God.... [At] the heart of this image is a new sprirtual dimension that...opens up for the viewer by directly engaging him or her in a visual look. It functions as an arrest of the passive, voyeuristic mode of the spectator.So why might my story justify the iconic pose?

In each story I am interested in that moment when the characters recognise where they have succeeded or failed. Sophie has overcomes fear, sets herself adrift. Claire knows she will never change, will never be able to give herself. Paul understands he has been defeated by chance, crushed, and worse, it is not personal. Each of these moments is about their relationship to the universe. They see where they stand.

Am I justified? I shall see.

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Antonioni and 'temp mort'

Just recently I finally managed to see Antonioni's Red Desert.

As I have been busy getting ready for the workshop in December I have been thinking of the idea of what has been called temp mort, which is seen in Red Desert and The Passenger.

The dead time is that moment when the characters have exited the scene and the camera lingers for too long on the empty space. In the conventional world of British cinema this would be considered bad form or sloppy editing, but here it suggests that this space is autonomous. It has its own reality and the story we are following just happened to occupy the space for a time.

(You can read much more about this idea in Seymour Chatman's excellent book on the director, Antonioni or, the Surface of the World)

A variation of this idea occurs in a number of Antonioni's film. In The Passenger, when Locke goes out into the desert to make contact with the rebels he sees a man coming towards him on a camel. He assumes that this man is his contact and as the man passes him the camera pans to follow the man. But it is a dead end. The man is not his contact and plays no part this story, though we assume that he has a story of his own.

For me the attraction is important for the first part of the three-part story, in which Sophie becomes aware of another reality, by the leaking of one into another. But in the story we only see two, whereas I want to suggest an awareness of all these possibilities, which I suppose is some moment of awareness of the infiniteness of the universe.

So temp mort would be used to suggest those moments when we become aware not just of one other possibilities, but an infinite number.

As I have been busy getting ready for the workshop in December I have been thinking of the idea of what has been called temp mort, which is seen in Red Desert and The Passenger.

The dead time is that moment when the characters have exited the scene and the camera lingers for too long on the empty space. In the conventional world of British cinema this would be considered bad form or sloppy editing, but here it suggests that this space is autonomous. It has its own reality and the story we are following just happened to occupy the space for a time.

(You can read much more about this idea in Seymour Chatman's excellent book on the director, Antonioni or, the Surface of the World)

A variation of this idea occurs in a number of Antonioni's film. In The Passenger, when Locke goes out into the desert to make contact with the rebels he sees a man coming towards him on a camel. He assumes that this man is his contact and as the man passes him the camera pans to follow the man. But it is a dead end. The man is not his contact and plays no part this story, though we assume that he has a story of his own.

For me the attraction is important for the first part of the three-part story, in which Sophie becomes aware of another reality, by the leaking of one into another. But in the story we only see two, whereas I want to suggest an awareness of all these possibilities, which I suppose is some moment of awareness of the infiniteness of the universe.

So temp mort would be used to suggest those moments when we become aware not just of one other possibilities, but an infinite number.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Photos from the film shoot

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

The new synopsis - 3 part version

Sophie (+ Paul)

For Sophie and Paul, it is over. They have had an ideal relationship and Paul struggles to understand how it went wrong. But for Sophie, that she is with Paul is down to chance. This means that good or bad could easily be reversed. All that stands in the way of these other possibilities is fear.

Claire, her friend, cannot understand how Sophie could throw Paul and a great relationship away. She is resentful, and reminds Sophie that it could've been her, Claire, that was with Paul. She could've been happy.

Paul recognises the danger to themselves - 'We are not an accident' - but it is too late. Sophie finds a way to overcome her fear and discovers another possible life.

Claire (-Paul)

In this story Claire has what she wanted. Paul. But they argue, Paul frustrated that Claire really is not committed or passionate about them together. Can Claire really change?

She sees her chance when her sister drops by unexpectedly. She is going away to get away from Nick, her boyfriend. He is too much. Can Claire look after her flat?

In Natalie's flat Claire finds photos of Nick. He has an intensity that is missing from her relationship with Paul. She decides to take a chance. She leaves Paul - just disappears and moves into Natalie's flat. And then she goes picking up the threads of Natalie's life, her friends, and work colleagues, and Nick. Her pretext is apologising for Natalie's bad behaviour, but her motive is to become someone else.

But can Claire finally change?

Paul (-Claire)

With Sophie, Paul knew who he was and what he wanted, but with Claire he is another man. For Paul, Claire's reticence and secrecy are part of her inability to commit to their relationship, driving Paul to despair. For Paul, his relationships are fundamental to who he is as a person. Perhaps out of peevishness, or just confusion he spends the night with a stranger, and returns in the morning, wondering about the consequences. But Claire has disappeared. He begins to search for her and his first visit is Sophie. Looking beyond her hostility he is struck by the unfairness of chance: he could've been with Sophie, he could've been someone else. Feeling the weight of this injustice, his life goes into a spiral. Paul indeed becomes someone else. He is unrecognisable.

For Sophie and Paul, it is over. They have had an ideal relationship and Paul struggles to understand how it went wrong. But for Sophie, that she is with Paul is down to chance. This means that good or bad could easily be reversed. All that stands in the way of these other possibilities is fear.

Claire, her friend, cannot understand how Sophie could throw Paul and a great relationship away. She is resentful, and reminds Sophie that it could've been her, Claire, that was with Paul. She could've been happy.

Paul recognises the danger to themselves - 'We are not an accident' - but it is too late. Sophie finds a way to overcome her fear and discovers another possible life.

Claire (-Paul)

In this story Claire has what she wanted. Paul. But they argue, Paul frustrated that Claire really is not committed or passionate about them together. Can Claire really change?

She sees her chance when her sister drops by unexpectedly. She is going away to get away from Nick, her boyfriend. He is too much. Can Claire look after her flat?

In Natalie's flat Claire finds photos of Nick. He has an intensity that is missing from her relationship with Paul. She decides to take a chance. She leaves Paul - just disappears and moves into Natalie's flat. And then she goes picking up the threads of Natalie's life, her friends, and work colleagues, and Nick. Her pretext is apologising for Natalie's bad behaviour, but her motive is to become someone else.

But can Claire finally change?

Paul (-Claire)

With Sophie, Paul knew who he was and what he wanted, but with Claire he is another man. For Paul, Claire's reticence and secrecy are part of her inability to commit to their relationship, driving Paul to despair. For Paul, his relationships are fundamental to who he is as a person. Perhaps out of peevishness, or just confusion he spends the night with a stranger, and returns in the morning, wondering about the consequences. But Claire has disappeared. He begins to search for her and his first visit is Sophie. Looking beyond her hostility he is struck by the unfairness of chance: he could've been with Sophie, he could've been someone else. Feeling the weight of this injustice, his life goes into a spiral. Paul indeed becomes someone else. He is unrecognisable.

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

Film class excercise

I have also been busy with 16mm film class, which sets out to introduce the students to the basics of a film shoot.

Last weekend was the shooting weekend and I took the opportunity to experiment with the shooting style.

I chose a scene from the revised outline when Sophie returns from her night excursion. The night before, in the middle of a discussion with Paul about how they met, Sophie disappears. She goes out into the night, and discover a parallel world (London at night). It is really about her overcoming fear and reaffirming her belief in chance.

Now that it is morning she returns to Paul. She wants to explain, but Paul is too angry to listen to her.While Paul understood that their marriage is over, he did not expect it to end this way. It is almost that she had an affair over the course of the night. She has betrayed their intimacy.

I had intended this scene to happen in Paul's office, but we had to take what was given to us, which was a Victorian house.

Paul enters the room and we decided (we being Todd, acting as my DOP) he would sit down. He is distraught but his way to deal with it is to pretend to be in control. He of course betrays himself several times in speech. The camera would look down on him, so that we could express his lack of status.

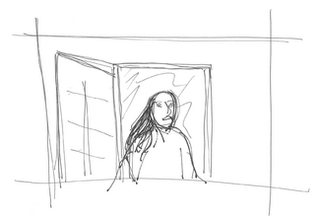

Sopie follows him, but though she has been here innumerable times before this morning she doesn't feel welcome. She hovers in the doorway, in the centre of frame, at a distance. We don't come any closer, as if we could not know what is happening with her any more than Paul. She is in the centre of the frame as if she didn't need anyone. And the camera looks up to her. Her status is higher than Pauls.

Our reverse is a close-up of Paul - we do know what is happening with Paul as he does most of the talking - and he is frame-right, with a void frame-left. As if he were expecting Sophie to fill that empty space.

At least that was the plan. But as we were rushed (when aren't you rushed on a film set?) we made mistakes. We shot Sophie first, and had Paul feed her his lines off-camera. But we forgot to have him sit down, so her eye-line was level to him, instead of looking down to him if were seated. To match the reverse we had to Paul standing as well. We missed out being able to use camera angle to express status in the scene.

The film is currently in the lab. Next week we will be editing, and I will post some images.

Thank you to my friends Ant and Mansi for coming out on a Saturday afternoon to act for me. And Todd Pacey my DOP, and everyone else in the class.

Last weekend was the shooting weekend and I took the opportunity to experiment with the shooting style.

I chose a scene from the revised outline when Sophie returns from her night excursion. The night before, in the middle of a discussion with Paul about how they met, Sophie disappears. She goes out into the night, and discover a parallel world (London at night). It is really about her overcoming fear and reaffirming her belief in chance.

Now that it is morning she returns to Paul. She wants to explain, but Paul is too angry to listen to her.While Paul understood that their marriage is over, he did not expect it to end this way. It is almost that she had an affair over the course of the night. She has betrayed their intimacy.

I had intended this scene to happen in Paul's office, but we had to take what was given to us, which was a Victorian house.

Paul enters the room and we decided (we being Todd, acting as my DOP) he would sit down. He is distraught but his way to deal with it is to pretend to be in control. He of course betrays himself several times in speech. The camera would look down on him, so that we could express his lack of status.

Sopie follows him, but though she has been here innumerable times before this morning she doesn't feel welcome. She hovers in the doorway, in the centre of frame, at a distance. We don't come any closer, as if we could not know what is happening with her any more than Paul. She is in the centre of the frame as if she didn't need anyone. And the camera looks up to her. Her status is higher than Pauls.

Our reverse is a close-up of Paul - we do know what is happening with Paul as he does most of the talking - and he is frame-right, with a void frame-left. As if he were expecting Sophie to fill that empty space.

At least that was the plan. But as we were rushed (when aren't you rushed on a film set?) we made mistakes. We shot Sophie first, and had Paul feed her his lines off-camera. But we forgot to have him sit down, so her eye-line was level to him, instead of looking down to him if were seated. To match the reverse we had to Paul standing as well. We missed out being able to use camera angle to express status in the scene.

The film is currently in the lab. Next week we will be editing, and I will post some images.

Thank you to my friends Ant and Mansi for coming out on a Saturday afternoon to act for me. And Todd Pacey my DOP, and everyone else in the class.

Where have I been?

Whew!

It has been a long time, but it has been necessary.

I have completely revised the treatment/outline and I am now planning a workshop with actors for the end of November/early-December.

What has changed?

I think more has changed than stayed the same, but essentially it is simpler and clearer than it was before. I was especially conscious of removing the tricks from the script, which only served to get in the way. For example, in Part 2 Claire had a twin sister, who disappears. Claire, seeing that her sister is somehow able to be the passionate, committed person she wants to be, decides to take on her life and pretend to be her. Yes, I know.

In the revised version she still takes on her sister's life, but they are not twins and it is not a case of stolen identity.

It has been a long time, but it has been necessary.

I have completely revised the treatment/outline and I am now planning a workshop with actors for the end of November/early-December.

What has changed?

I think more has changed than stayed the same, but essentially it is simpler and clearer than it was before. I was especially conscious of removing the tricks from the script, which only served to get in the way. For example, in Part 2 Claire had a twin sister, who disappears. Claire, seeing that her sister is somehow able to be the passionate, committed person she wants to be, decides to take on her life and pretend to be her. Yes, I know.

In the revised version she still takes on her sister's life, but they are not twins and it is not a case of stolen identity.

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Long break

It has been along time, what with summer holidays, and the madness of work. I have begun a new draft, which is simpler and more focused. And also I have begun to find locations, and will begin to post images in due course.

Camera tricks

Thinking more on the The Passenger, and the scene that is known as the glideback (described below) - I wondered, does it matter that the glideback happens within one shot? I understand the objective is to contain a sense of truth and time, and that cutting would be considered a simple camera trick. But doesn't the audience accept the whole construct of cinema as a trick? And what bigger trick could there be in Locke climbing over the camera crew, doing a quick change, and then leaping out onto the terrace?

Tuesday, July 11, 2006

Tarkovsky and editing and rythm

So I am back with Sculpting in Time, thinking back to the same question: how do I shoot this thing?

I am looking to Tarkovsky to articulate some things I felt or thought. More develop than articulate.

First a rejection of Eisenstein and montage. He connects this with his rejection of the author's presence in the work.

Furthermore, montage suggests that the editor creates the rythm by this juxtaposition.

Tarkovsky would argue that the rythm exists within the shot itself:

I will struggle to find my own method.

I am looking to Tarkovsky to articulate some things I felt or thought. More develop than articulate.

First a rejection of Eisenstein and montage. He connects this with his rejection of the author's presence in the work.

When in October [Eisenstein] juxtaposes a balalaika with Kerensky, his method has become his aim...The construction of the image becomes an end in itself, and the author proceeds to make a total onslaught on the audience, imposing his own attitude to what is happening.He would reject the idea of montage - that juxtaposition of two ideas creates a third - because the result is an idea. The authors.

Furthermore, montage suggests that the editor creates the rythm by this juxtaposition.

Tarkovsky would argue that the rythm exists within the shot itself:

Although the assembly of the shots is responsible for the structure of the film, it does not, as it is generally assumed, create its rhythm.So I would reject the conventions. Master shot, medium two-shot, close-up. These always seemed false to me, someone else's solution to someone else's problem.

The distinctive time running through the shots makes the rhythm of the picture; and rhythm is determined not by the length of the edited pieces, but the pressure of the time that runs through them. Editing cannot determine rythm (in this respect it can only be a feature of style); indeed, time courses through the picture despite editing rather than because of it. The course of time, recorded in the frame, is what the director has to catch in the pieces laid out on the editing table.

I will struggle to find my own method.

Sunday, July 09, 2006

One-part version: just on the wrong side?

A friend of mine read the one-part version and said: I don't buy it.

Well, I don't buy it either. I wonder if part of my struggle in choosing is that I am unconvinced by this version.

And now, looking back on that scene in Mirror, I wonder if the flaw in the story is that we are witness to Sophie living that other life. Perhaps it would be better if, like Ignat, we are only aware of it from this side?

(This does mean that we are not witness to any less detail about this other life, only that we see from Sophie on this side.)

Well, I don't buy it either. I wonder if part of my struggle in choosing is that I am unconvinced by this version.

And now, looking back on that scene in Mirror, I wonder if the flaw in the story is that we are witness to Sophie living that other life. Perhaps it would be better if, like Ignat, we are only aware of it from this side?

(This does mean that we are not witness to any less detail about this other life, only that we see from Sophie on this side.)

Thursday, June 29, 2006

Antonioni's The Passenger

I was very excited to finally see Antonioni's The Passenger.

As you can imagine I was attracted to the theme's of identity.

I was particularly taken with this scene, described below.

Locke (Jack Nicholson) is a television reporter working in Central Africa. He is there trying to get a story about a rebel movement, trying to overthrow the government.

But he has been frustrated at every turn, and it is clear that Locke is not a happy man.

He returns to his hotel and knocks on the door of another westerner, Robertson. But Robertson is dead.

Locke has decided to switch identities. Become Locke. He takes Robertson's passport and returns to his own room.

Locke at his desk. The two passports in front of him.

Locke looks down at the table, first at his own passport - the camera pans right to left - and then at Robertson's.

We hear a knock. Locke looks up. We think someone is at the door.

We hear Locke answer, but not speak. A flashback?

We hear another man. This voice must be of Robertson. Locke is remembering when he met Robertson.

Locke cuts out Robertson's passport photo.

We listen as Locke explains why he is in Africa.

From Locke the camera pans across to the chair. We see a tape recorder, and if we look carefully we see that it is running. This is not a memory of Locke's. It is a recording of a conversation.

Locke at his desk again. He looks up and the camera pans right to left again. This time to the window. Through the window we can see an empty terrace, and the desert in the background.

A man comes onto the terrace. We do not know yet that this is Robertson. He speaks to someone we cannot see.

Then Locke comes and stands next to Robertson. They look out into the desert.

We have slipped back in time.

Robertson tells Locke that he has been in so many places that it doesn't make any difference anymore. The key theme of the film is established.

We cut to a doorway. Locke and Robertson come and continue to speak.

Robertson tells Locke that he has no family, nor friends.

Locke goes off left to retrieve another drink. Robertson continues to speak to him, off-camera (he looks to our left).

Then the camera pans left to right. For the first time.

We return to Locke at the table. We have slipped forward in time.

Locke turns off the recorder.

The next scene is off Locke taking Robertson's body from his own room to Locke's. Robertson will become Locke. Locke, Robertson.

The switch is complete.

As you can imagine I was attracted to the theme's of identity.

I was particularly taken with this scene, described below.

Locke (Jack Nicholson) is a television reporter working in Central Africa. He is there trying to get a story about a rebel movement, trying to overthrow the government.

But he has been frustrated at every turn, and it is clear that Locke is not a happy man.

He returns to his hotel and knocks on the door of another westerner, Robertson. But Robertson is dead.

Locke has decided to switch identities. Become Locke. He takes Robertson's passport and returns to his own room.

Locke at his desk. The two passports in front of him.

Locke looks down at the table, first at his own passport - the camera pans right to left - and then at Robertson's.

We hear a knock. Locke looks up. We think someone is at the door.

We hear Locke answer, but not speak. A flashback?

We hear another man. This voice must be of Robertson. Locke is remembering when he met Robertson.

Locke cuts out Robertson's passport photo.

We listen as Locke explains why he is in Africa.

From Locke the camera pans across to the chair. We see a tape recorder, and if we look carefully we see that it is running. This is not a memory of Locke's. It is a recording of a conversation.

Locke at his desk again. He looks up and the camera pans right to left again. This time to the window. Through the window we can see an empty terrace, and the desert in the background.

A man comes onto the terrace. We do not know yet that this is Robertson. He speaks to someone we cannot see.

Then Locke comes and stands next to Robertson. They look out into the desert.

We have slipped back in time.

Robertson tells Locke that he has been in so many places that it doesn't make any difference anymore. The key theme of the film is established.

We cut to a doorway. Locke and Robertson come and continue to speak.

Robertson tells Locke that he has no family, nor friends.

Locke goes off left to retrieve another drink. Robertson continues to speak to him, off-camera (he looks to our left).

Then the camera pans left to right. For the first time.

We return to Locke at the table. We have slipped forward in time.

Locke turns off the recorder.

The next scene is off Locke taking Robertson's body from his own room to Locke's. Robertson will become Locke. Locke, Robertson.

The switch is complete.

Wednesday, June 28, 2006

Tarkovsky and the other side

The other night, unable to sleep, I put on Mirror my laptop, and placed it next to my pillow. I often find that trying to read subtitles in a difficult Russian film at 3am makes sleep a little easier.

This night it didn't work. I went through Mirror for the 10th time. What I had forgotten was the amazing scene with Ignat, and Maria Nikolaevna. Ignat's mother leaves him in his father's flat waiting for Maria. He sees his mother out the door, crosses the hallway and is disturbed by the the sound of cups. Maria is there, at the table, looking for Ignat. There is a maid as well. And what was an empty hallway in the previous shot now includes chairs, mirrors, and lighting. She asks him to read from a book on one of the shelves, Pushkin's letters. As she listens the light in the room changes, as if the sun were slipping in and out from behind clouds.

Just as he finishes there is a knock at the door. Or rather Ignat looks to the door as if there was a knock. And Maria encourages him to open the door. But I could hear no knock.

He opens the door. It is an old woman. She looks confused, apologises, says she has the wrong flat and leaves (she looks like Ignat's grandmothers - we see photos of her later).

Ignat closes the door and goes back into the flat, but Maria has gone.

On the table, a circle of steam remains from where Maria's tea cup had rested. It quickly disappears.

This night it didn't work. I went through Mirror for the 10th time. What I had forgotten was the amazing scene with Ignat, and Maria Nikolaevna. Ignat's mother leaves him in his father's flat waiting for Maria. He sees his mother out the door, crosses the hallway and is disturbed by the the sound of cups. Maria is there, at the table, looking for Ignat. There is a maid as well. And what was an empty hallway in the previous shot now includes chairs, mirrors, and lighting. She asks him to read from a book on one of the shelves, Pushkin's letters. As she listens the light in the room changes, as if the sun were slipping in and out from behind clouds.

Just as he finishes there is a knock at the door. Or rather Ignat looks to the door as if there was a knock. And Maria encourages him to open the door. But I could hear no knock.

He opens the door. It is an old woman. She looks confused, apologises, says she has the wrong flat and leaves (she looks like Ignat's grandmothers - we see photos of her later).

Ignat closes the door and goes back into the flat, but Maria has gone.

On the table, a circle of steam remains from where Maria's tea cup had rested. It quickly disappears.

Thursday, June 15, 2006

Coincidence and the past - II

Later, Claire and Robert are over for dinner.

Claire (now joined in this debate, it involves her too, it was crucial moment in her life as well) can produce polaroids of her flat. Of parties.

The debate is enlarged, revised, extended.

What would Claire feel?

This is the moment she lost Paul to Claire (and as a consequence ended up with Robert, a dead-end).

She would fear being drawn into their domestic squabble.

She would wonder at her current situation and speculate at how it could have all been different (and then we see the power of the three-part version of the story, as we see this to be a false hope. Her relationship with Paul is not any better than the one with Robert).

All this time Robert is in the background, listening.

Claire is aware of injustice and the universe.

She gets angry. At this game playing.

What the hell does it matter?

This is more likely. She pretend anger with Robert, but she is more angry with the universe.

Why has she been left out of the scenario/been done such an injustice?

Claire (now joined in this debate, it involves her too, it was crucial moment in her life as well) can produce polaroids of her flat. Of parties.

The debate is enlarged, revised, extended.

What would Claire feel?

This is the moment she lost Paul to Claire (and as a consequence ended up with Robert, a dead-end).

She would fear being drawn into their domestic squabble.

She would wonder at her current situation and speculate at how it could have all been different (and then we see the power of the three-part version of the story, as we see this to be a false hope. Her relationship with Paul is not any better than the one with Robert).

All this time Robert is in the background, listening.

Claire is aware of injustice and the universe.

She gets angry. At this game playing.

What the hell does it matter?

This is more likely. She pretend anger with Robert, but she is more angry with the universe.

Why has she been left out of the scenario/been done such an injustice?

Sunday, June 11, 2006

Three-part version: Paul (-Claire) synopsis

Paul (-Claire)

With Sophie, Paul knew who he was and what he wanted, but with Claire he is another man. For Paul, Claire's reticence and secrecy are part of her inability to commit to their relationship, driving Paul to despair. His relationship with Claire is fundamental to who he is as a person. Paul sets out to take revenge, spends the night with a stranger, and returns in the morning, wondering about the consequences. But Claire has disappeared, and when Paul sets out to find her, and learn who she was really was, his life goes into a spiral. It's as if he were no longer complete. It might look like a game, but for Paul it is critical. He does everything to find her, and with Sophie's help, tracks down Claire's twin sister, Natalie. His reception is not friendly. Claire and Natalie did not enjoy the novelty of being twins. They found it a challenge to their identity. But with a little charm Paul is able to able to talk to Natalie. He intrigues with the question, why did it not work with Claire and himself? It is as if Paul was smitten. If he can't have Claire perhaps he can have Natalie? Or is it really Claire? No matter.

With Sophie, Paul knew who he was and what he wanted, but with Claire he is another man. For Paul, Claire's reticence and secrecy are part of her inability to commit to their relationship, driving Paul to despair. His relationship with Claire is fundamental to who he is as a person. Paul sets out to take revenge, spends the night with a stranger, and returns in the morning, wondering about the consequences. But Claire has disappeared, and when Paul sets out to find her, and learn who she was really was, his life goes into a spiral. It's as if he were no longer complete. It might look like a game, but for Paul it is critical. He does everything to find her, and with Sophie's help, tracks down Claire's twin sister, Natalie. His reception is not friendly. Claire and Natalie did not enjoy the novelty of being twins. They found it a challenge to their identity. But with a little charm Paul is able to able to talk to Natalie. He intrigues with the question, why did it not work with Claire and himself? It is as if Paul was smitten. If he can't have Claire perhaps he can have Natalie? Or is it really Claire? No matter.

Three-part version: Claire (-Paul) synopsis

Claire (-Paul)

But what if this were not true for someone? What if, no matter who they were with they were the same? That they didn't really change for they were with, and by implication, they didn't care. They weren't really affected by that person. This is Claire, Sophie's friend. In Sophie (+Paul) Claire's relationship with her husband is falling apart. She looks at Sophie's nearly perfect relationship with Paul and wonders what is wrong with her? What's more, when Sophie met Paul he was going out with Paul. But now in Claire (-Paul) she is with Paul. What would it be like to feel so completely for someone? The kind of relationship her twin sister Natalie has with Nick? Claire gets her chance when Natalie disappears. She takes up Natalie's life, and begins a relationship with Nick. Why? After the disastrous relationship with Paul she needs to find out if she can care.

But what if this were not true for someone? What if, no matter who they were with they were the same? That they didn't really change for they were with, and by implication, they didn't care. They weren't really affected by that person. This is Claire, Sophie's friend. In Sophie (+Paul) Claire's relationship with her husband is falling apart. She looks at Sophie's nearly perfect relationship with Paul and wonders what is wrong with her? What's more, when Sophie met Paul he was going out with Paul. But now in Claire (-Paul) she is with Paul. What would it be like to feel so completely for someone? The kind of relationship her twin sister Natalie has with Nick? Claire gets her chance when Natalie disappears. She takes up Natalie's life, and begins a relationship with Nick. Why? After the disastrous relationship with Paul she needs to find out if she can care.

Three-part version: Sophie + Paul synopsis

Sophie + Paul

Sophie has a great relationship with Paul. He knows who he is, and makes those around him comfortable. They live in the sky above the Thames, a hi-rise set of flats from where they can see river and the tidal barrier. But it all begins to fall apart one day when they begin to look into the circumstance of their first meeting: coincidence. This realisation means that any relationship, even a good one, is arbitrary, it could as easily not be. Paul recognises the danger. 'We are not an accident' and 'It's not that I believe in destiny, it's that I can believe in 'coincidence'. But it is too late. This begins to erode Sophie and Paul's relationship. At the same (or because of it?) they are 'haunted' by people or events from this 'other life'.

Sophie has a great relationship with Paul. He knows who he is, and makes those around him comfortable. They live in the sky above the Thames, a hi-rise set of flats from where they can see river and the tidal barrier. But it all begins to fall apart one day when they begin to look into the circumstance of their first meeting: coincidence. This realisation means that any relationship, even a good one, is arbitrary, it could as easily not be. Paul recognises the danger. 'We are not an accident' and 'It's not that I believe in destiny, it's that I can believe in 'coincidence'. But it is too late. This begins to erode Sophie and Paul's relationship. At the same (or because of it?) they are 'haunted' by people or events from this 'other life'.

Haunted by the other 'life'

Both versions of this story begin centre on the the theme that each possibility of our life is equally legitimate. There are endless other lives, universes, or threads. We might have become these, or we may one day become them.

And in this story all the characters are in one way haunted by these other lives. I am deliberately playing on the horror/thriller genre here.

A recurring incident in Sophie's and Paul's story: one night Paul spys a car parked below their hi-rise flat. The engine is running and the wipers wave back and forth. Though it is impossible to see clearly because of the dark and the rain, both Paul and Sophie believe that the driver is parked there looking up at them in their flat, and that the driver is a woman. Paul is angry and threatened. He wants to confront the woman, though he cannot say why. Sophie is frightened and would rather hide in the bedroom than confront her.

At the end of Paul's and Sophie's story Sophie is again at the window and the car is below.

In the car is Sophie too. Another thread. She is not with Paul (or with anyone). She lives in a house (not a flat) and struggles for direction (unlike the first Sophie who is so certain about what she is).

And in this story all the characters are in one way haunted by these other lives. I am deliberately playing on the horror/thriller genre here.

A recurring incident in Sophie's and Paul's story: one night Paul spys a car parked below their hi-rise flat. The engine is running and the wipers wave back and forth. Though it is impossible to see clearly because of the dark and the rain, both Paul and Sophie believe that the driver is parked there looking up at them in their flat, and that the driver is a woman. Paul is angry and threatened. He wants to confront the woman, though he cannot say why. Sophie is frightened and would rather hide in the bedroom than confront her.

At the end of Paul's and Sophie's story Sophie is again at the window and the car is below.

In the car is Sophie too. Another thread. She is not with Paul (or with anyone). She lives in a house (not a flat) and struggles for direction (unlike the first Sophie who is so certain about what she is).

Coincidence and the past

One part of this story charts the downward spiral of Sophie's and Paul's relationship once they recognise that their near-perfect relationship rests on the coincidence and chance that brought them together.

Some of my critics accepts this, others don't. The doubters would say that it would not matter how the relationship began. What counts is the strength of their relationship. I would say that accepting a universe governed by chance and coincidence would make anyone doubt the veracity of any kind of relationship. What would this near-perfect relationship be based on? Such a thing could not exist.

So Sophie and Paul begin by disagreeing over the circumstances of their meeting. Paul must believe in fate because he cannot accept chance. That would be the end of them and he recognises the danger. Sophie believes in chance unconsciously, and if aware of the danger cannot turn from the conviction of the idea. They begin to re-rehearse the events of their meeting, a party at Claire's flat (Sophie's friend). What music was playing? Where were they sitting? How did they begin to talk? What sparked the relationship?

The debate can revolve around one incident - an accident? A lamp is pushed over. How did it happen? Paul can claim he did.

It altered the situation. A shared experience.

Paul spoke to Sophie. They had ignored each other until now. Did Sophie dislike him for Claire's sake?

Paul believed that Sophie was jealous.

Some of my critics accepts this, others don't. The doubters would say that it would not matter how the relationship began. What counts is the strength of their relationship. I would say that accepting a universe governed by chance and coincidence would make anyone doubt the veracity of any kind of relationship. What would this near-perfect relationship be based on? Such a thing could not exist.

So Sophie and Paul begin by disagreeing over the circumstances of their meeting. Paul must believe in fate because he cannot accept chance. That would be the end of them and he recognises the danger. Sophie believes in chance unconsciously, and if aware of the danger cannot turn from the conviction of the idea. They begin to re-rehearse the events of their meeting, a party at Claire's flat (Sophie's friend). What music was playing? Where were they sitting? How did they begin to talk? What sparked the relationship?

The debate can revolve around one incident - an accident? A lamp is pushed over. How did it happen? Paul can claim he did.

It altered the situation. A shared experience.

Paul spoke to Sophie. They had ignored each other until now. Did Sophie dislike him for Claire's sake?

Paul believed that Sophie was jealous.

Friday, June 09, 2006

Why Tarkovsky and the long-take?

I need to say more about the theme.

One tenet: that we are different people with different people. Who we are and who we might become is dependent upon who we are with now and who we are with (or without) in the future.

Time and chance define our identity. In the three-story version each thread is equally valid. One may show the characters in one situation (in part one Sophie and Paul are a couple) and another in a different situation (Paul and Claire are a couple, at least temporarily, and Sophie, Claire's best friend, doesn't particularly like Paul).

Other threads overlap. In two, Paul is the person Claire left behind. In three it we see much of the same story from his viewpoint. Much is the same. Some is different.

Each thread of time is equally valid.

This is where I make the leap to the long-take: each captures a segment of each thread. Each is true, for that moment in time. One does not supersede the other. Each successive shot amplifies the effect. The edits would come naturally, joining two captures of time. The approach to the shooting, the shooting style, cannot be divorced from the essence of cinema.

You can see how this would be the case with number of short-takes. I feel that the weight of time would be absent, dispersed. The edits more a case of convention than anything else. Coverage.

At the same time I am not suggesting that each take = the scene, as in Haneke's Code Unknown.

Taking this approach into the studio with the actors, the construct of the long-take will shape the scene, pushed in one direction or another.

One tenet: that we are different people with different people. Who we are and who we might become is dependent upon who we are with now and who we are with (or without) in the future.

Time and chance define our identity. In the three-story version each thread is equally valid. One may show the characters in one situation (in part one Sophie and Paul are a couple) and another in a different situation (Paul and Claire are a couple, at least temporarily, and Sophie, Claire's best friend, doesn't particularly like Paul).

Other threads overlap. In two, Paul is the person Claire left behind. In three it we see much of the same story from his viewpoint. Much is the same. Some is different.

Each thread of time is equally valid.

This is where I make the leap to the long-take: each captures a segment of each thread. Each is true, for that moment in time. One does not supersede the other. Each successive shot amplifies the effect. The edits would come naturally, joining two captures of time. The approach to the shooting, the shooting style, cannot be divorced from the essence of cinema.

You can see how this would be the case with number of short-takes. I feel that the weight of time would be absent, dispersed. The edits more a case of convention than anything else. Coverage.

At the same time I am not suggesting that each take = the scene, as in Haneke's Code Unknown.

Taking this approach into the studio with the actors, the construct of the long-take will shape the scene, pushed in one direction or another.

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

How do I make this thing?

This is not all theory. I am truly struggling to conceive of a way to approach the shooting of this film.

Think of Wong Kar-Wai's In the Mood for Love. The couple are seen between lampshades, around doorways, below the jackets hanging in the closed. Snapped. Glimpsed. They are repeatedly reframed. Seen from this the same position, but with a different frame, different focal length.

What is this about? (I am under no illusion that there is great idea trying to break forth).

This is about memory. It is unreliable. Partial. Fragmented.

Also look at Michael Haneke's Code Unknown. Yes, long-takes, but more than that: each shot is a scene. Usually it the world of one character (though the street scene includes all the characters of the film, in some manner).

For example: a father at the farmhouse table eating a simple dinner. The young son has disappeared. Not a word. Ungrateful. There is a noise off. The son has returned. He passes the father and sits at other end. Says nothing. The camera does not follow him, does not establish him in the scene. It stays with the father. The father looks at him. He goes to the counter, gathers some dinner for the son, returns to the table, then follows the father into the toilet. He needs to hide his disappointment.

What about Tidal Barrier?

Imagine a framed shot. Sophie, one of the main characters. From this close-up a jump-cut to an empty frame. Slight pan to the right and the frame is found.

What is this about?

Another Sophie at another time.

The colour of her face could be different between the shots. Her features are different.

Or. The second shot, the same position, but a different focal length. She is further away - we are no nearer to understanding her - her face has changed (the colour, her face is in shadow), before we can know her she has changed again.

Or return to Tarkovsky. If the fundamental of cinema is capturing time, and the long-take is the evident way of doing so then is the long-take the central tenet of the shooting style of this film?

Think of Wong Kar-Wai's In the Mood for Love. The couple are seen between lampshades, around doorways, below the jackets hanging in the closed. Snapped. Glimpsed. They are repeatedly reframed. Seen from this the same position, but with a different frame, different focal length.

What is this about? (I am under no illusion that there is great idea trying to break forth).

This is about memory. It is unreliable. Partial. Fragmented.

Also look at Michael Haneke's Code Unknown. Yes, long-takes, but more than that: each shot is a scene. Usually it the world of one character (though the street scene includes all the characters of the film, in some manner).

For example: a father at the farmhouse table eating a simple dinner. The young son has disappeared. Not a word. Ungrateful. There is a noise off. The son has returned. He passes the father and sits at other end. Says nothing. The camera does not follow him, does not establish him in the scene. It stays with the father. The father looks at him. He goes to the counter, gathers some dinner for the son, returns to the table, then follows the father into the toilet. He needs to hide his disappointment.

What about Tidal Barrier?

Imagine a framed shot. Sophie, one of the main characters. From this close-up a jump-cut to an empty frame. Slight pan to the right and the frame is found.

What is this about?

Another Sophie at another time.

The colour of her face could be different between the shots. Her features are different.

Or. The second shot, the same position, but a different focal length. She is further away - we are no nearer to understanding her - her face has changed (the colour, her face is in shadow), before we can know her she has changed again.

Or return to Tarkovsky. If the fundamental of cinema is capturing time, and the long-take is the evident way of doing so then is the long-take the central tenet of the shooting style of this film?

Monday, June 05, 2006

No. First...

No. First, before I can go there, I need to speak of something more.

Before the practicalities of lenses and long-takes vs short-takes, what might be my attitude to the whole thing?

I have been rereading Tarkovsky's Sculpting in Time. I think that I was interested in what he had to say about this attitude:

Quoting Tarkovsky, quoting Gogol:

I have not been at this business long, but I have shocked at the laziness, fear, and insecurity with which the industry approaches the business of making film. I suppose I might be more sympathetic to those that argue for tradition, or simplicity, who say they have no desire to experiment, they are practitioners, not artists, who truly believe that they are doing a service to the mainstream, entertaining them, making them smile, if they actually did know that tradition.

I once had director of photography tell me that we could not do this or that because we would be breaking the fourth wall. I come from theatre, and there you quickly learn what that term means, but he clearly did not. I would have forgiven him but for the ferocity and stubborness of his position, when he would tell me that this is the way you would do things, this is tradition when this was cleary not true.

I spent a lot of time in the edit suite trying to correct these fundamental errors. I wasn't experimenting either.

But Tarkovsky would go further than this. Even these traditions were false:

Now I think on the films of Tarkovsky. What about that amazing long-take in Solaris, as Berton makes his way into the city, through tunnels and across overpasses? Or the closing shot of Mirror, in the field before the house, the grandmother and her grandchildren? Yes, there is much more here, but first is this Tarkovsky capturing time?

I might decide to dismiss Tarkovsky (I mean how can I do a tracking shot? They are too bloody expensive), but at least it begins the dialogue.

Before the practicalities of lenses and long-takes vs short-takes, what might be my attitude to the whole thing?

I have been rereading Tarkovsky's Sculpting in Time. I think that I was interested in what he had to say about this attitude:

Artistic creation demands of the artist that he 'perish utterly', in the full, tragic sense of those words.From these you can be certain what Tarkovsky made of artist as centre of the work: it is a mistake.

Quoting Tarkovsky, quoting Gogol:

...it is not my job to preach a sermon. Art is anyhow a homily. My job is to speak in living images, not in arguments. I must exhibit life full-face, not discuss life.More on this, as he writes of Raphael's Sister Madonna:

...for the artist's thought is there for the reading: all too unambigious and well-defined. One is irritated by the painter's sickly allegorical tendentiousness hanging over the form and overshadowing all the purely painterly qualities of the picture.So that is fairly clear.

I have not been at this business long, but I have shocked at the laziness, fear, and insecurity with which the industry approaches the business of making film. I suppose I might be more sympathetic to those that argue for tradition, or simplicity, who say they have no desire to experiment, they are practitioners, not artists, who truly believe that they are doing a service to the mainstream, entertaining them, making them smile, if they actually did know that tradition.

I once had director of photography tell me that we could not do this or that because we would be breaking the fourth wall. I come from theatre, and there you quickly learn what that term means, but he clearly did not. I would have forgiven him but for the ferocity and stubborness of his position, when he would tell me that this is the way you would do things, this is tradition when this was cleary not true.

I spent a lot of time in the edit suite trying to correct these fundamental errors. I wasn't experimenting either.

But Tarkovsky would go further than this. Even these traditions were false:

A mass of preconceptions exists in and around the profession. And I do mean preconceptions, not traditions: those hackneyed ways of thinking, that grow up around traditions and gradually take them over. And you can achieve nothing in art unless you are free from received ideas.So you have to start again. What is the essence of cinema? What is cinema about?

...the birth of cinema was when man found the means to make an impression of time.Further:

And often as he wanted, to repeat it and go back to it. He acquired a matrix for actual time.

The cinema image, then, is basically observation of life's facts within time, organised according to the pattern of life itself, and observing its time laws.The word facts is important. So often we hear that this or that is symbolic. This is usually just laziness. Cinema's power is not in the symbol:

The purity of cinema, its inherent strength, is revealed not in the symbolic aptness of images (however bold these may be) but in the capacity of those images to epxress a specific, unique, actual fact.So dismiss symbols. There is no ambiquity, something standing for another. There is first the fact.

Now I think on the films of Tarkovsky. What about that amazing long-take in Solaris, as Berton makes his way into the city, through tunnels and across overpasses? Or the closing shot of Mirror, in the field before the house, the grandmother and her grandchildren? Yes, there is much more here, but first is this Tarkovsky capturing time?

I might decide to dismiss Tarkovsky (I mean how can I do a tracking shot? They are too bloody expensive), but at least it begins the dialogue.

Friday, June 02, 2006

Some other challenges

Much of what I have written in the treatments describes images and sequences, which are difficult to test on paper.

The only way I can know if they work is to shoot them.

Similarly, the scenes between Sophie, Paul, and Claire must be tested with actors. These improvisations need to be shot as close as possible to the shooting strategy.

What is the shooting strategy? More to come.

The only way I can know if they work is to shoot them.

Similarly, the scenes between Sophie, Paul, and Claire must be tested with actors. These improvisations need to be shot as close as possible to the shooting strategy.

What is the shooting strategy? More to come.

Locations, London, flow, time and chance

This weekend I will be scouting for locations in East London, around Canary Wharf, East India Station, The Dome, Woolwich Road, the Tidal Barrier (of course), and up to Thamesmead. I will do stills and some video. I will uploads the stills, if they are any good.

Apart from the locations described in the treament, I am looking for images that may help me to develop the theme of the story. Flow. Time. Chance.

I will also try to capture a part of London that is all too must a part of the city: parts of the city that lack identity, no there there, as Jane Jacobs would say. They are places where people come and go, without being able or without wanting to take part in the time of the city. Their passing will go unnoticed.

These areas contrast with parts of London where the past seems to have been pressed right into the bricks.

These areas have always existed, but what is fascinating about Canary Wharf is that they are constructing this phenomenon in shiny glass and steel.

Apart from the locations described in the treament, I am looking for images that may help me to develop the theme of the story. Flow. Time. Chance.

I will also try to capture a part of London that is all too must a part of the city: parts of the city that lack identity, no there there, as Jane Jacobs would say. They are places where people come and go, without being able or without wanting to take part in the time of the city. Their passing will go unnoticed.

These areas contrast with parts of London where the past seems to have been pressed right into the bricks.

These areas have always existed, but what is fascinating about Canary Wharf is that they are constructing this phenomenon in shiny glass and steel.

Thursday, June 01, 2006

The one-story version - Tidal Barrier

A story about relationships, exploring the possibilities of who we might have been and who we might become.

Sophie has a great relationship with Paul. He knows who he is, and makes those around him comfortable. They live in the sky above the Thames, a hi-rise set of flats from where they can see river and the tidal barrier.

But it all begins to fall apart one day when they begin to look into the circumstance of their first meeting: coincidence.This seemingly innocent fact sets in motion a realisation that who they are, and thus who they have become is arbritrary. They could've as easily lived another life. Paul understands the threat and his desperation is driven further by the appearance of one of these other lives: for many nights now Sophie has seen a stranger parked below their flat, watching her. Sophie is frightened, Paul is angry, both instinctively understand the implications. One night they decide to confront the woman in the car. They are separated, and Sophie ends up wandering about the world of London at night. Both frightened and intoxicated by the freedom, she takes a part in this new world, in and around the Thames, and here she finds another life she would've lived without Paul.

Sophie has a great relationship with Paul. He knows who he is, and makes those around him comfortable. They live in the sky above the Thames, a hi-rise set of flats from where they can see river and the tidal barrier.

But it all begins to fall apart one day when they begin to look into the circumstance of their first meeting: coincidence.This seemingly innocent fact sets in motion a realisation that who they are, and thus who they have become is arbritrary. They could've as easily lived another life. Paul understands the threat and his desperation is driven further by the appearance of one of these other lives: for many nights now Sophie has seen a stranger parked below their flat, watching her. Sophie is frightened, Paul is angry, both instinctively understand the implications. One night they decide to confront the woman in the car. They are separated, and Sophie ends up wandering about the world of London at night. Both frightened and intoxicated by the freedom, she takes a part in this new world, in and around the Thames, and here she finds another life she would've lived without Paul.

It is not so straightforward

I am actually struggling through two different versions of the story.

One is described previously, but the other focuses on Sophie and Paul in the first story. I call this version the one-part version.

I was optimistic that 'three part version' had finally developed enough that everyone would agree it was clearer. But no. Some feel that one version works, some the other version is better.

One is described previously, but the other focuses on Sophie and Paul in the first story. I call this version the one-part version.

I was optimistic that 'three part version' had finally developed enough that everyone would agree it was clearer. But no. Some feel that one version works, some the other version is better.

The three-story version - Tidal Barrier

Three stories about relationships, exploring the possibilities of who we might have been and who we might become.

Sophie, Paul, and Claire, a triangle, with the addition of chance, place and time.

I am with this person. Where do I end, and the other begins? Who might I have been alone? By myself?

What if we had never met? How did we meet? Is there any way to believe in destiny? Was it only chance? If so, then it just as easily and legitimately might not have been. Such knowledge and belief can destroy the best relationship. After all, how can you wake every day and think it was only accidental that I am with this person?

And time. How might I change over time? Would the person I became want to/need to be with this person?

Sophie, Paul, and Claire, a triangle, with the addition of chance, place and time.

I am with this person. Where do I end, and the other begins? Who might I have been alone? By myself?

What if we had never met? How did we meet? Is there any way to believe in destiny? Was it only chance? If so, then it just as easily and legitimately might not have been. Such knowledge and belief can destroy the best relationship. After all, how can you wake every day and think it was only accidental that I am with this person?

And time. How might I change over time? Would the person I became want to/need to be with this person?

What else is there?

What else is there?

I have pages of notes, someone of which I am using as blog entries. I am also in the process of developing a photo project focused on the locations and ideas that I am developing in the story. I have some vague ideas of creating a photoblog.

There will be a website with some background information about the film, which will make sense of some of the entries to come.

I have pages of notes, someone of which I am using as blog entries. I am also in the process of developing a photo project focused on the locations and ideas that I am developing in the story. I have some vague ideas of creating a photoblog.

There will be a website with some background information about the film, which will make sense of some of the entries to come.

What is there?

What is there?

I have been developing what I loosely refer to as treatment (a prose document which can be anywhere from one page to 100 pages and usually has no dialogue). Now film professionals will tell you that a treatment can be almost anything that will assist in the development of a script, but will scream you can do that if you take them at your word.

I would say that my treatment is more along the lines of a short story because my intention is to use as a basis for improvisation with actors.

Someone wrote of my treatment at the moment the confusion in it makes it a frustrating read.

This is probably true.

I have been developing what I loosely refer to as treatment (a prose document which can be anywhere from one page to 100 pages and usually has no dialogue). Now film professionals will tell you that a treatment can be almost anything that will assist in the development of a script, but will scream you can do that if you take them at your word.

I would say that my treatment is more along the lines of a short story because my intention is to use as a basis for improvisation with actors.

Someone wrote of my treatment at the moment the confusion in it makes it a frustrating read.

This is probably true.

What is this?

What is this?

I am making a film. This blog is about the development of the thoughts and ideas that will go into developing a story, and this story will eventually become the film.

I am making a film. This blog is about the development of the thoughts and ideas that will go into developing a story, and this story will eventually become the film.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)