As you can imagine I was attracted to the theme's of identity.

I was particularly taken with this scene, described below.

Locke (Jack Nicholson) is a television reporter working in Central Africa. He is there trying to get a story about a rebel movement, trying to overthrow the government.

But he has been frustrated at every turn, and it is clear that Locke is not a happy man.

He returns to his hotel and knocks on the door of another westerner, Robertson. But Robertson is dead.

Locke has decided to switch identities. Become Locke. He takes Robertson's passport and returns to his own room.

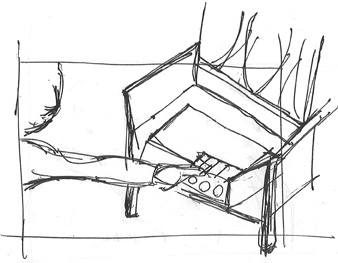

Locke at his desk. The two passports in front of him.

Locke looks down at the table, first at his own passport - the camera pans right to left - and then at Robertson's.

We hear a knock. Locke looks up. We think someone is at the door.

We hear Locke answer, but not speak. A flashback?

We hear another man. This voice must be of Robertson. Locke is remembering when he met Robertson.

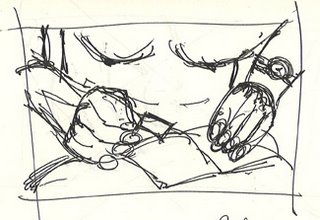

Locke cuts out Robertson's passport photo.

We listen as Locke explains why he is in Africa.

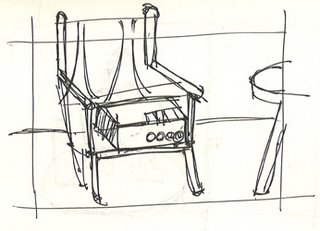

From Locke the camera pans across to the chair. We see a tape recorder, and if we look carefully we see that it is running. This is not a memory of Locke's. It is a recording of a conversation.

Locke at his desk again. He looks up and the camera pans right to left again. This time to the window. Through the window we can see an empty terrace, and the desert in the background.

A man comes onto the terrace. We do not know yet that this is Robertson. He speaks to someone we cannot see.

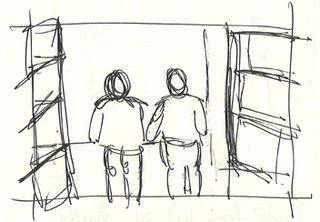

Then Locke comes and stands next to Robertson. They look out into the desert.

We have slipped back in time.

Robertson tells Locke that he has been in so many places that it doesn't make any difference anymore. The key theme of the film is established.

We cut to a doorway. Locke and Robertson come and continue to speak.

Robertson tells Locke that he has no family, nor friends.

Locke goes off left to retrieve another drink. Robertson continues to speak to him, off-camera (he looks to our left).

Then the camera pans left to right. For the first time.

We return to Locke at the table. We have slipped forward in time.

Locke turns off the recorder.

The next scene is off Locke taking Robertson's body from his own room to Locke's. Robertson will become Locke. Locke, Robertson.

The switch is complete.